In Downtown Gallup, New Mexico, there lies a street that only exists for about three or four blocks. This is Coal Avenue, and it is here that I will tell you about my friend, Shane.

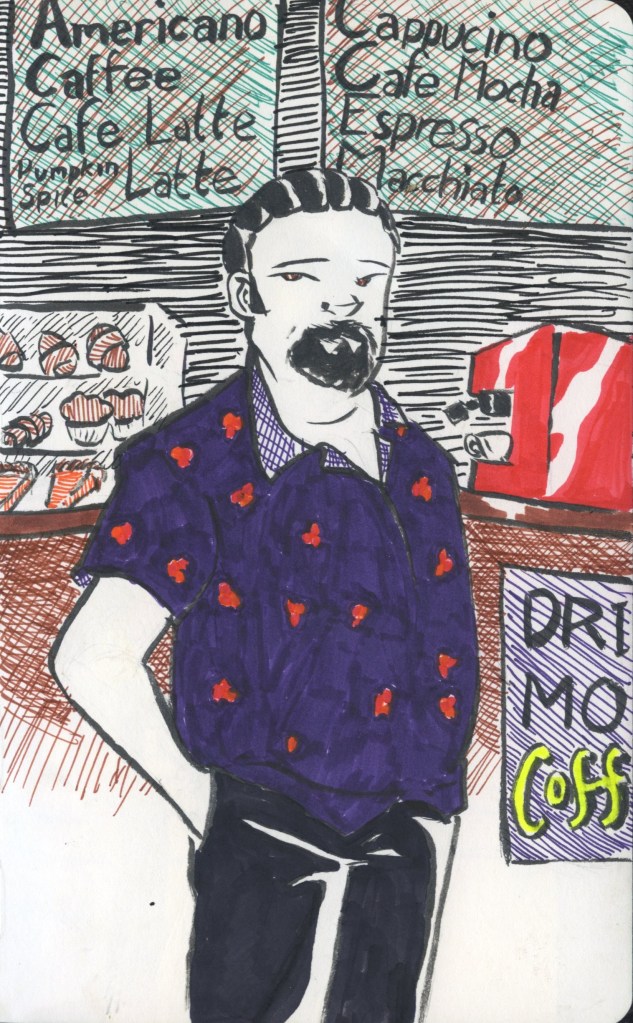

Picture a second-story window, and standing before it on the inside is a young man, no older than twenty. He’s not particularly tall, and he’s bulky, but not unattractively so. He wears his blond hair down to his chin, and his clothes, usually denim, were covered in paint. He sticks his head outside and yells out, “I thought I told you to leave Angelita outta this!”

On the sidewalk, a tall, skinny teenager with big glasses and a long, blond ponytail shouts back something misogynist and vulgar, despite that the two boys are not the former, but are definitely the latter.

Vinny was Shane. He was an aspiring artist who returned to Gallup after many years of homelessness, wandering through eighties and nineties alternative culture like Forrest Gump. For a time, he lived in a blue Volkswagen Beetle. He later surfed couches, and eventually got a job waiting tables at the most popular restaurant in Gallup (it was Italian) and an apartment of his own, a studio apartment that he eventually decorated with a bed, a kitchen table, and pastel smears all over the walls. He even had business cards. I will forever remember them because they read:

Shane Van Pelt

Artist/Writter

When I met him, I had already found my identity in the darker side of Alternative culture. Meeting Shane at a football game altered that course, so instead of a path of black clothes and self-destruction, I became something more bohemian.

Shane had a lot of patience for me, who grew up with undiagnosed and untreated mental illnesses. When I went away to college, he was not the best pen-pal. But he did do things like leave phone messages at the front desk of my dorm informing me that Angelita was pregnant.

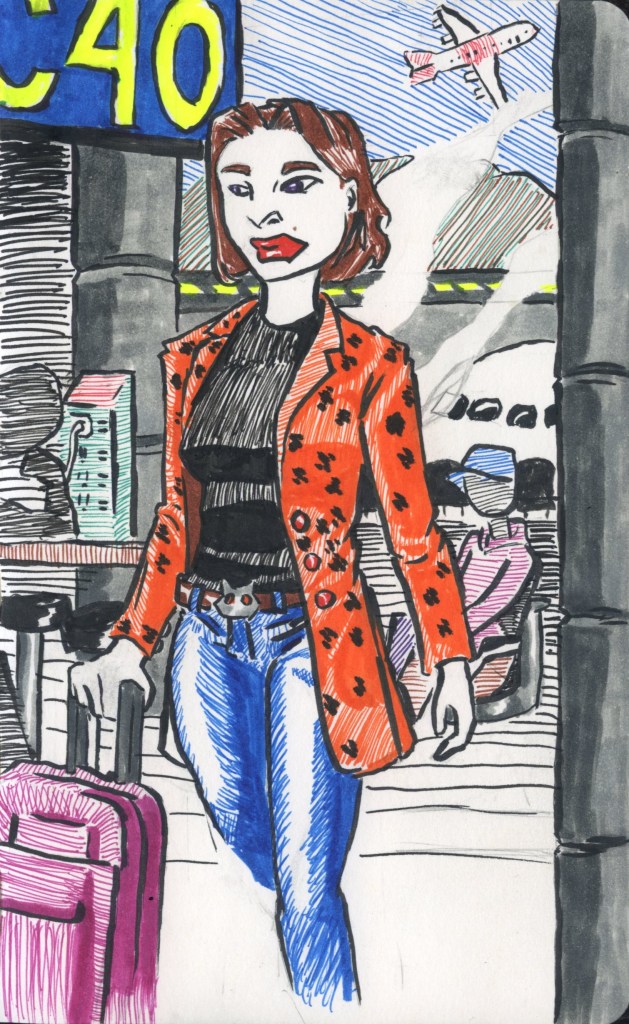

After his marriage, which I heard about third-hand, he and Elizabeth moved to New York City. He visited me a handful of times in college, shuttling back and forth from there to Gallup. People, seeing us together, assumed we were brothers. We were. He made quick friends with many of my friends as well because he was so freaking charming.

I ended up in New York, with nothing but a little bit of money and my friendship with him. He showed me around Manhattan and showed me where to buy weed. In fact, my first weekend there, he took me into Harlem to pick some up, and we didn’t know at the time that Louis Farrakhan’s Million Youth March was taking place. “Try to look inconspicuous,” he told me.

Elizabeth knew people, and during one of the first weeks I was living New York Adjacent, she took us to a party. Shane and I were the only people either of us knew, and he retreated solo as soon as we walked in the door. I found a corner and suffered, and an intellectual in his thirties approached me and asked if Shane and I were a “team.” As in a band or a writing duo? Even apart, we were simpatico.

I wanted to be a comic book illustrator, but I didn’t know how to draw. Shane, despite the raw stick figures I was starting with, was the first person to call me an artist. And if someone as cool and talented as Shane Van Pelt says it, it must be true.

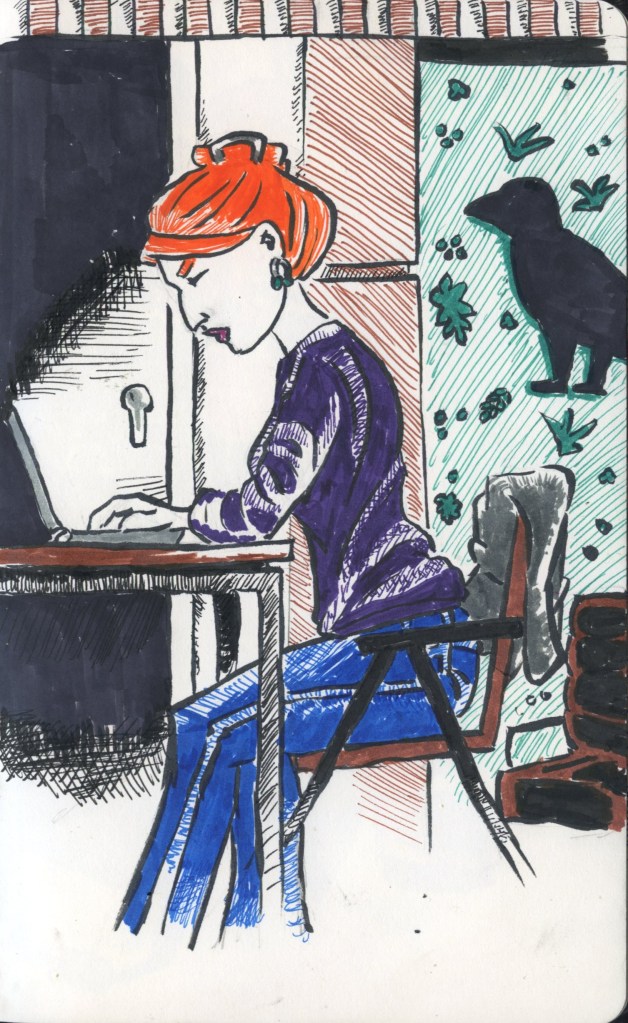

He, Elizabeth, and their newborn Ava retreated Upstate, and some of the best three-day weekends I ever spent were in his drafty house in Binghamton, after I shelled out sixty bucks for a bus ticket. Together, we’d sit in his studio and work on one of two screenplays, Convenience Store Maniac or The Day the West Went Dry. The former is lost to history, which is too bad because I thought it was brilliant. The latter we’ll get back to.

When I got married, there was one person I wanted at my side, and that was Shane. I have to say, though, twenty years later, I’m still disappointed in his Best Man speech. What was important, though, was that he was there.

For personal reasons I won’t go into and because Shane is a bad pen-pal, we had drifted apart during my marriage. However, we talked a lot more after my divorce (i.e. once every few months), and no time had passed between. We were still insulting each other in gross, not-Woke ways, and we could talk about anything.

In 2022, I recalled that some of the best memories I had were hanging out in Shane’s studio and doing screenplay jam sessions. I took a trip to see him that summer, and for seven days, we extended our two-hour movie into a series. He said he knew people at Netflix. I didn’t care either way. I just wanted the quality time with my best friend.

He called me more frequently than that afterward, about once a month. However earlier in 2024, he told me he was committing to talking more often, and the calls came biweekly. He told me about his plans in Wheeling, West Virginia, which would bring him a short bus ride from me. He had to deal with some property issues because somehow, the high school dropout I knew who used his tips to buy art supplies had property issues now.

The last time I talked to Shane, it was this past Monday. He had called me, scared, because he’d been without some of his medications, and he was starting to feel the withdrawal. He told me he would be getting his medications Tuesday, so I told him that this was a moment. The moment would become a memory, like all his memories, and life would go on. The last thing I said to my best friend was a lie.

Since Shane has lived several lives apart from mine, I don’t know many of his friends or relatives. I met Elissa, his mother, once, and I knew he was devoted to her. Elizabeth has been a good friend to me with the patience of Job. I haven’t seen his daughter Ava since she learned how to walk over a three-day weekend and instructed me how to move Daddy’s paintbrushes from one jar to another. I have never forgotten that lesson, even though I couldn’t understand the words coming out of her mouth.

If you go to his website and you somehow dig up his essay about grunge (Shane’s filing systems made sense to him, at least), you’ll see a storyteller chock full of story. After reading said essay, I have been constantly riding him to write his memoirs. Somehow, Shane has packed about eighty years of living into the fifty he had, and I hope the person who inherits his computer at the very least finds more of these essays. He was also working on a novel, and I was really excited to read it when it finished.

There’s so much more I want to tell you about him. I have stories, like the time we stood on the street, Shane scratching pastels onto a rogue piece of drywall and me, narrating the process in my best (okay, worst) Joe Pesci voice. Or how he stole that boombox from a house I was sitting for, and I was the one who got in trouble. Or the joy on my face the day after Elizabeth Fraser of the Cocteau Twins hugged a painting he made for her.

Shane was an accomplished artist, with shows all over the world. Thirty years ago, I watched him go from painting nudes of Sherilyn Fenn to his current style, whatever that is. Is it Cubist? Surrealist? Impressionist? Outsider? It’s none of those things. Shane was, and always will be unique.

Shane Van Pelt died Saturday, November 9, at approximately 1:00 a.m. Mountain Time.

He had met me in every stage of my life, and he still liked me. He was probably the best friend I’d ever had. I don’t know what I’m going to do without him.