Of everything I saw, there is one thing about that morning I can never forget: the weather was perfect. The summer had been difficult for me. I lost my job, and I had sunk into a deep depression, and my relationship with Andrea was getting rocky. The weather was full of peace, the sky was blue, and the leaves were still green. My step picked up a spring. I sat down at my desk and stuffed envelopes with energy and panache. That day started out so full of hope.

Tag Archives: September 11

Chapter 6

[For context: the narrator, Nora, is a veteran assassin who thinks Julie Andrews is a righteous bitch, and Edgar is the guy she rescued from a suicide attempt.]

“Let me be the first to welcome you back,” Edgar said as he left the PATH turnstile.

I laughed “Well, let me just say I’m honored to be here.”

He led me out of the station. “The financial district is really my hood. I have done a lot of temping here.”

If you draw a shape that cannot possibly exist in a three-dimensional universe, it’s called a tesseract. You could conceivable fit infinity into one. The corridors under the World Trade Center were a tesseract. The only reason I emerged into the plaza between the towers was because I had a guide. I barely found the PATH station on my own from the subway.

We stepped off of the World Trade Center campus and went one block north. “We’re here,” he told me.

I looked around, a frown on my face. “Are you sure, because the only thing I see is a bodega.”

He nodded.

“That bodega makes the best bagel?” I asked.

He grinned and gestured me inside the building. In the back was a guy, probably Armenian, who said, “What you want.” It wasn’t a question.

Edgar reminded me, “They have everything, and everything.”

“I’ll take a plain bagel with butter,” I told the scowling man behind the counter.

While he sliced my bagel in half, Edgar said, “You have the choice of all the bagel flavors in existence, and you went with plain.”

“If they can’t make a good plain bagel,” I replied, “what good are they?”

The Armenian man put the bagel on a rolling toaster and asked Edgar, “What you want?”

“Cinnamon bagel with peanut butter,” Edgar said.

I smirked. “I never took you for a cinnamon bagel guy.”

He smirked back. “How was The Princess Diaries, by the way?”

“On reflection, I did walk into that one.”

We left the bodega and wandered the streets, unwrapping and biting into our bagels. It might not have been the best plain bagel in the city, but it was the best I’d ever had. I swallowed. “I’m coming back to this place as many times as—”

BOOM!

The ground shook under our feet.

“What the hell was that?” I demanded, looking left and right for some answers. South of us, I could make out people screaming.

Edgar looked straight up and dropped his bagel. “Fuck?”

I followed his gaze to the Twin Towers, half of which were on fire. How the fuck did something like that happen? It was probably a plane, a big one. Was the pilot drunk? Having a heart attack? Wasn’t there a copilot to keep this kind of thing from happening? That airline was going to get the pants sued off of it.

What was worse was that whole subway lines were going to be shut down over this. No cab was going to come here to pick me up, and I was wearing heels. How was I supposed to get home?

We stared at the fire for a long time, maybe even a half hour, and then a plane flew into the other tower, making that same BOOM and shaking the ground. The screams got louder.

Okay, that was not an accident. Somebody purposefully bloodied America’s nose. I was actually impressed.

The most important thing I needed to do was get out of there. Anywhere outside of the Financial District, I didn’t care. Just pick a street and go north.

Edgar took a step in the direction of the World Trade Center, and I grabbed his arm. “The way out is that way,” I told him, pointing in the opposite direction.

“I need to make sure they’re okay.”

“Everybody on the top of both towers is screwed,” I said, “and we’re probably going to get lung cancer from breathing in all this asbestos.”

“You think there’s asbestos?” he asked.

“It was built in the seventies, of course there’s asbestos. Now let’s get the fuck out of here.” Not wanting to wait around to explain it to him, I dragged him up the street with no idea where I was going. I needed a cab, a subway entrance, something.

I know I had been doing this a while because the first subway station I saw was City Hall. I pulled out my MetroCard, which was pay-per-ride, not unlimited, so I could swipe twice to get us both through.

While we waited, Edgar craned his neck to look outside, but he didn’t have a good view.

I said, “Look, Edgar, I have no idea what’s going on, but I know I can get you out of here. I will keep you safe.”

“I need to help those people,” he muttered.

“Edgar!” I snapped, holding his shoulders and forcing him to look at me, “the Twin Towers are on fucking fire. All those people on those floors were instantly burned alive or even vaporized. You’re just an out-of-shape writer without a story. I love you, Edgar, but the best thing you can do now is get out. We’ll get you to Hoboken somehow.”

The train arrived, and we stepped onboard. Considering that the previous stop was Cortland Street, inside the World Trade Center complex, I’d expected a lot more riders, but we were alone. Exhausted, I plopped down on one of the hard, plastic seats. Edgar sat beside me.

“I need to do something,” he sighed as the train pulled away from the station.

“Join the army as soon as we figure out who we’re going to war with.” Who would we go to war with? If both towers were struck by planes, that meant terrorists. I didn’t know much about terrorists, just that they attacked other countries, not ours. Destroying two of the tallest buildings in the United States was pretty ambitious for any terrorist. As long as the US treated this as a law-enforcement situation and not as a war, we had a chance of figuring out who did this and bringing them to justice. However, if we went to war with a stateless adversary, then we were in danger of another Vietnam. “On second thought, don’t join the military.”

The driver of the train didn’t announce our stop. They were preoccupied. However, we pulled into the Canal Street station as usual. The doors hung open for a minute, and, just before they closed, Edgar sprang to his feet and outside. I tried to follow, but he had timed it perfectly.

He mouthed, “Sorry!”

“Edgar, you idiot!” I screamed, hopefully loud enough to be heard through the shatter-proof windows. When the train rolled out of the station, I stated, “I’m going to kill you.” Coming from me, that was no idle threat.

I had a lot of patience, which was part of the reason I was so good at my job. I called upon that patience while the train rolled uptown, until we hit the next stop, Prince Street, close to Houston Street, which meaning not that close at all to the World Trade Center, which was where Edgar was headed. I calmly exited the train, walked up street level, kicked off my heels, and ran, barefoot, down Broadway.

Man was not meant to run barefoot on a sidewalk, and I could feel the abrasions on my feet. I’d soak them in Epson salt after I saved Edgar’s life so I could strangle him to death with my own hands.

While catching my breath, I saw one person tell another person, “They got the Pentagon!”

How many planes did these guys have? The amount of coordination involved in this endeavor was mind-boggling. Someone in a cave somewhere figured out how to bring the United States to its knees. If they had asked me to plan a way to freak America out to the bone, I never would have had the imagination to think of this. At the risk of giving them too much credit, these guys were evil geniuses.

Whoever it was, I’d kill them. Save the troops, save the billions they’d spend going to war with an invisible enemy. Just send me in there. Give me a week, problem solved.

I put up with the blisters on the soles of my feet as I started to encounter scores of people going in the opposite direction. But he closer I got, the more people were just gawking. I suppose they had a good reason. What were they planning on doing if the towers fell over? Me, I would be in a different borough, if it weren’t for—

“Edgar!” I shouted.

That was definitely him. He turned around and smiled. “Nora, I have to help these people.”

“There’s got to be five hundred firefighters in the towers right now,” I told him. “What do they want with a skinny, out-of-shape gothic boy?”

He studied the entrance to the South Tower far away and took a step toward it. I snagged his arm with my hand and held him in place. He looked at me with pleading eyes.

I said, “I did not save you from killing yourself so you can turn around and kill yourself.”

“Let me go, Nora.”

“But I barely had you,” I said.

“You don’t know me, Nora.”

I let him go. He ran off into the distance to the tower.

“Don’t you fucking die, Edgar,” I whispered. “I’ll wait right here.” He got farther away. “I’ll wait right—”

I felt like I was underwater, and a muffled roar, groans, and collisions were attacking me, and something shoved me onto my back onto the street, and the world switched to gray, with flecks of black and white, making it look like, as William Gibson would say, a TV tuned to a dead channel. A few feet away, I could make out a hunched-over shadow, and then another and another. The only thing I could think of to do was find something like a wall and anchor myself to that.

Using some of that patience I rely on, I waited until the air thinned out, and I could see for more than three feet. It was now closer to ten, maybe fifteen. I decided to take my chances, and I headed for the area I remembered the South Tower.

However, when I got there, the only thing I could see was the shadow of a section of the towers’ latticework shell sticking straight up out of the ground. The South Tower wasn’t there. I looked over my shoulder and saw more latticework and no North Tower.

I sighed, “I got to sit down.” I found what appeared to be a corner of the building and sat on that. “Ugh,” I grunted, coughing in the ash-filled air, “I am definitely getting cancer from this.”

You kill one person, you’re a bad guy. You kill ten people, you’re a monster. Is there a word for the six thousand people they probably killed today? I couldn’t think of anything big enough. I could safely say that I was literally a mass murderer, and I looked like a saint compared to these guys, whoever they were.

I got up and headed home. The searing pain on the soles of my feet focused me as I lurched forward, completely covered in ash—the remains of the people in the building, one foot in front of the other. I couldn’t let my mind wander like I usually would because the pain and the effort took so much concentration.

“Step, move my weight, step, move my weight …”

I wasn’t sure how I did it, but I opened the door to my apartment. With every two steps, I shed another article of clothing until I stood in the bathroom, naked. I turned on the shower, let it heat up, and stepped inside. Without a little cold water to cool it down, the water scalded. Good, maybe if it got hot enough, I could scrub the remains of thousands of people off of my body.

With crimson skin, I finally left the shower and laid down on my bed. It was still light out, but I didn’t have it in me to do anything tonight, not even sleep.

He was gone. I felt like I had finally found something I had never been looking for. I knew him for a week, and we only spent a few hours with each other. He got a coldblooded killer to care about something. And now he was nothing but ash.

“I don’t even know his last name,” I told the empty room.

Time passed, and my phone rang. Not my work phone, but my personal phone. I picked it up and barked, “Only one person has this number, and—”

“It’s me.”

Neither one of us spoke for a while.

“I thought,” I said with an eerie calm, “you were dead, Edgar. I’ve been mourning you for hours.”

“I underst—”

“Holy shit!” I shouted as loudly as I possibly could. “You’re alive! I thought I saw you die.”

“I don’t know what to tell you,” he said. “Here I am.”

“Where’s here?” I asked. “Were you able to get back to Hoboken?”

“I’m at Union Square,” he told me. “There’s plenty of places to rest here.”

“Wait right there,” I said and hung up. I called the number for Brown Limousines and demanded, “I want a car to take me to Fourteen Street, no excuses.”

“Traffic is blocked below Fourteenth Street,” the dispatcher told me.

“It’s a good thing I’m only going to Fourteenth Street then.”

The car arrived in four minutes, and we were quickly at Union Square. The driver generously volunteered to wait for me to pick up my friend, and I quickly found a half-asleep Edgar on the lawn. I had to partially carry him, despite the fact that it was my feet that were destroyed looking for him, and we made it to the car.

The driver wasn’t having it. “You think I want to clean that shit off of my leather seats? Get a cab if you want to drive somewhere.”

“Do you even know what’s been happening today?”

“No, but traffic below Fourteenth is cut off. Is there a marathon or something?”

I closed my eyes impatiently. “Two planes crashed into the Twin Towers, and they don’t exist anymore. Apparently something like this happened at the Pentagon, but I heard that in passing, so take it with a grain of salt. The world is ending, and you’re going to begrudge a guy who was close enough to get covered in ash because you’re worried your car is going to get dirty? You’re going to do this today of all days? Where’s your generosity? Your charity?” That last bit was laying it on a little thick, but I was in a mood.

“I get it, I get it,” the driver muttered. “You can ride in my car. If you come to me covered in ash any other day but today, you’re walking home. Do you understand me?”

“I’ll tell him when he wakes up,” I said.

“This is just great,” the driver grumbled. “All the streets downtown will be closed for Allah knows how long, and the detours are going to go all the way up to the Fashion District. And don’t forget all the emergency vehicles, snarling up traffic. I tell you, I’d be better off getting blown up in the Twin Towers.”

Living in Infamy

For the first few years, the mantra was “Never Forget.” Cruising through Facebook and Tumblr today, it’s clear we’ve forgotten. Last year, I wrote about how September 11 is fading because it’s not the worst thing that’s happened to this country in the past twenty-five years. But it’s the worst thing that’s happened to me.

After twenty-two years and an assortment of pressures in my current life, I don’t really have anything to say today. This wouldn’t be the first time. For the first ten years I only wrote two journal entries on this day, one in 2005, one in 2011. Since then, I’ve written about it inconsistently. All eight blog entries about it can be found here:

However, as I’ve noted the significance of the day receding in the public consciousness, I think it’s important for me to mark the occasion by not going into work and by writing something.

Last year, I penned a novel in need of a serious rewrite about a female assassin. I wanted to set it in New York, but I wanted to set it in my New York (see September 11, 2011), so I set it in 2001. And because it might be cathartic, I set it in September of 2001. As my memories of the actual event and the TV coverage become blurred, I wrote “Chapter 6: Living in Infamy.” It’s longer than my usual posts, but it would mean a lot if you took the time to read it.

Blackjack Anniversary

My neighbors are all women in their late twenties, and they have the priorities people their age have, like dating and FWBs. We have a picnic table in our backyard, and they like to hang out there when the weather is good, sometimes with the company of gentlemen callers. A handful of times, when I’m taking out the trash, they will invite me to sit with them. A handful of those times, I’ve taken them up on it. I never say anything, I just listen.

On one occasion, the subject of September 11 came up. They weren’t kind. They treated it as an overrated, overhyped spectacle that people needed to get over. If I really wanted to make them awkward, I could have told them where I was that day, but I’d probably no longer get invites to enjoy their show. Plus they’re kids. When I was twenty-seven, I wasn’t a kid, but twenty-seven-year-olds now are kids. Prior to September 11, 2001, I was pretty flippant about Vietnam and the people affected by it.

I wasn’t offended, and that’s because I’ve been writing a novel where two twenty-six-year-old women fall in love. They’re in Battery Park, New York City, and the subject of the 9/11 Memorial comes up, and it occurred to me as I was writing that the Twin Towers on fire looked just like a movie. If you were a kid, say five years old, when this happened, how would you be able to tell the difference? Maybe I should ask a Baby Millennial/Geriatric Zoomer.

My main character: “September 11 is Generation X’s defining moment, like Vietnam was for Boomers.”

Love Interest: “What’s the Millennials’ defining moment?”

Main Character. “Look around. Take your pick.”

If disaster and disaster came my way just as I’m becoming an adult or trying to settle down with my young family, and if the people in power don’t represent your viewpoint anymore and are legislating hard against people like you, somehow two buildings falling down doesn’t seem like that big a deal.

September 11 is old enough to drink or, in select states, purchase cannabis. What’s happened is that it, like every memory, grew hazy with time. September 11 was bad, but twice as many Americans died in Iraq fighting a war that was proven beyond a reasonable doubt to be manufactured by people who profited immensely from it and were never punished. Almost that amount died in New Orleans when a hurricane they should have been prepared for ravaged a US state, and many more died because relief efforts were so poorly planned. And so on, to this decade, when a virus spread through the country, killing almost a million people, which could have been contained if leadership wasn’t incompetent. Now we have mega-billionaires bending the country to their will and a reactionary minority preparing to take rights away from all of us.

All that in mind, what does 9/11 mean to me? It’s not the worst thing to happen to this country in the past thirty years. Why do I feel something heavy in the pit of my stomach every time I see the date on a calendar? Is it because I was there? Because everybody’s memory of September 11 is one tower burning while a plane crashes into the second, while mine is from a different angle, on the ground, looking up buildings so tall, you couldn’t see the top, now covered in flames and smoke.

My experience with COVID was disappointing, to say the least. I was hoping to be bedridden for a few days, but all I got was a headache. But twenty-one years ago, for about four hours in the morning, the world was on fire. Strangers would grab you and yell in your face that they destroyed the Pentagon! They’re taking out the bridges! And the guilt. I actually believed I could run in there and help people. I didn’t care how or what I did, I thought I could help. Instead, I ran. I’ve made a lot of decisions in my life, but that was probably the smartest.

This essay doesn’t have a clear thesis. Like September 11, there’s no lesson to be learned here. It reveals nothing about our humanity. My generation likes to think they’re jaded, latchkey kids who’ve seen it all. But we were spoiled. America won the Cold War and was riding high when we were young. We were the punching bags of the Boomers until Millennials came along with their avocado toast, and that’s really as bad as it got for us collectively. (Individually, I know a lot of Gen-Xers who’ve suffered unfairly in life, but as a whole, we’ve done pretty well.) Our innocence died on September 11, and as a result, the subsequent generations never really had any. Maybe that’s why I go back to that day, again and again, starting in August every year. It was the morning that changed everything, even for the Millennials and Zoomers who don’t realize it.It was the morning America got so scared that it went completely mad and hasn’t recovered since.

Imagine growing up in that.

A Gift of Platinum and China

I struggled for a year about what I should do for the twentieth anniversary of the September 11 attacks. The most obvious thing to do would be to go to New York and be there for it, but I really can’t. It’s not because of money or finding a place to stay or anything but because it’s not my New York. My New York is trapped in amber from 1998 to 2004 when subway fares were $1.50 and the Freedom Tower hadn’t even been conceived yet. My New York doesn’t exist anymore, just like the Jeremiah of 2001 doesn’t exist anymore either, and that is a mixed blessing. I thought of myself as a New Yorker for years after I moved on, but not anymore. I’ve lived in the greater DC area for thirteen years (minus the two-and-a-half I lived in Qatar), far longer than I lived in New York, or even New Mexico, which I consider my home (I won’t be going back there either). I made the decision I would stay home for the anniversary of the day the world ended.

New York has always been a city in flux, so it’s not only unrecognizable from 2001, but it’s also unrecognizable from 2014, the last time I was there. I think that really showed itself in the weeks following September 11, 2001. The Twin Towers had dominated the skyline for decades, looking like, as Donald Westlake described them, an upside-down pair of trousers. Suddenly, it was gone, and all that was left was wreckage that was still recognizable as the World Trade Center. After we finished running away, screaming, and when the dust settled, we had to return to our lives. There was an updated subway map on September 17. By September 24, I was back to work a block and a half from a smoking crater, having to take a ferry there from Hoboken because the PATH train went directly into the World Trade Center. We got used to the Towers’ absence really quickly, and life went on.

Except life didn’t. I was in a relationship at the time that was irreparably damaged by the events of that day and limped along for another five months out of sheer inertia before falling down and dying. The problem was she was shaken to her core by the attack, and she needed comfort. I was unable to give it because I had shut down my emotions to get me through that day, and they didn’t come back on for a long time. It didn’t help that I was drunk and high constantly for the two weeks following the incident. Not dealing with it was how I chose to deal with it.

As a sidebar, I met someone who would become one of my most fondly remembered friends as a result of that day. At the end of the month, someone threw a party for all the September birthdays that didn’t get celebrated that year, and I met this really cool young woman and wanted to be her friend right away. She was celebrating because 9/11 gave her the kick in the pants she needed to divorce her terrible spouse. As with everything, there were good side effects.

The vaccine-denying, election-overturning, polarized hate-fest that is modern America has a lot of roots in this day. There are a lot of milestones on the road to where we are now—the nomination of Ronald Reagan for president in 1980, the ascension of Newt Gingrich to Speaker of the House in 1995, and so on. However, as a result of being president on one of the worst days in American history, George W. Bush, who was well on his way to becoming a one-term president, became a two-term president, and the Republican Party really got the hang of hateful polarizing tribalism. Rudy Guiliani would have been a footnote in history had he not stood on the rubble and started barking orders. Do you remember flag pins? Do you remember what would happen to you politically if you didn’t wear one?

On the twentieth-anniversary year, we finally left Afghanistan, the country we destroyed in retaliation for the attack. When we first invaded in 2002, the Taliban was in control. In 2021, the Taliban is in control. As much dread as I feel for the people stuck there under this oppressive regime, I can’t help but shake my head and wonder what the fucking point of all of it was.

Osama bin Laden has been quoted saying he wanted to bankrupt the United States, not conquer it. People who were watching American troops loot Saddam’s palace a year and a half later were thinking, “U! S! A! We won! Take that, bin Laden!” But we have gone trillions in debt occupying countries and not actually helping anything. All of the precious freedoms President Bush said “they” hated were being signed away by the PATRIOT Act and other bits of legislation. Dick Cheney’s company Halliburton robbed the off-the-books budget and didn’t even pretend they weren’t doing it. Osama bin Laden wasn’t a stupid man. He accomplished his mission.

September 11 is a formative chapter in my life as a young man. I’m not a young man anymore. In the 2000 election, George W. Bush and Al Gore fought like gladiators over prescription-drug benefits for seniors. The summer of 2001, the most front-page headlines were about Gary Condit, a U.S. Representative who was suspected of killing his aide. America has not been young for a long time, but in 2000, 2001, the stakes seemed a little lower. We can’t go back to those days again. I can’t go back to those days again. I could go to New York, but it will be as foreign to me as San Francisco was when I went this summer. It would be like going back after a while to that coffee shop you frequented until you left the neighborhood, and the barista who knew you by name doesn’t recognize you anymore. In fact, we’re going to let Pearl Jam play us out with a little number from 1993, “Elderly Woman Behind the Counter in a Small Town.”

I seem to recognize your face

Haunting, familiar yet

I can’t seem to place it.

Cannot find a candle of thought to light your name

Lifetimes are catching up with me

Oh, Mercy, Mercy Me

Here we are, six months into the pandemic, and a whole lot of people are acting like idiots. This spring, armed men invaded state capitals because they literally wanted to get a haircut. I was talking to someone about how this was the way life was now, and something occurred to me.

The last time that a major upheaval happened in our lives was nineteen years ago today. The whole country shut down under the weight of this horrible act of aggression. The peace and prosperity of the nineties was over (the prosperity had already ended pretty much as soon as Bush was sworn in, but that’s not how we remember it), and we were all going to make sacrifices of our old lives in the face of this new reality.

But in actuality, we didn’t. Life returned to normal pretty much instantly, and I’m not talking about extra airport security or Islamophobia or the incredibly unpopular president becoming a superhero to most of the country. I’m talking about day-to-day life. We could go to restaurants, go to movies, get the oh-so-important haircut. The words of comfort and aid from our president were not “Ask not what your country can do for you,” but rather, “Go shopping.” The MTA had an updated subway map out in about a week. We lost some of our freedoms, but we didn’t really miss them. The only people who gave anything up were those that rushed headlong into the recruiter’s office and found themselves in Afghanistan and Iraq, but, in general, those were the kinds of people who were going to join the military anyway, so no real difference.

Eighteen and a half years later, an invader came to our shores again to rob us of our way of life, and Americans, remembering how this kind of thing goes, were expecting a quick return to normalcy. We don’t like change.

But the fact of the matter is, everything changed, and it will be forever different. One day, in a year, maybe more, the stores may open up all the way again, and schools may be taking students in without having to go online again after a rash of infections pop up, but things won’t be the same. Many Mom and Pop stores will be forever shut down, to be replaced by a centralized, corporate structure. The kinds of people who are freaking out about masks will wield even more political power. We’re already seeing America’s billionaires getting exponentially richer over the past six months, and they’ll do anything not to lose their money. This is how life is now. We won’t be wearing masks forever, but the changes to the way we live our lives are fundamental. It is never going to be the way it was before.

And we, as Americans, can’t deal with that.

Memories Fade, Part 2

I hate this day. I hate it so much. In August, I usually start dreading it and wondering how I’m going to feel this year. It’s been eighteen years. 9/11 is old enough to vote. It doesn’t haunt me most of the time, it doesn’t drive me to drink. I hardly think of it anymore. But I’ll never forget. And still that date rolls around.

It’s just a normal day anymore, with the exception of Twitter and Facebook remembrances (like this one), but I want the world to stop. I don’t want to go to work. I don’t want anybody to go to work. I don’t want people to have Meet-ups or dates or parties. I don’t even know what I want people to do instead, I just don’t want them pretending that nothing happened today.

Maybe it’s because I was there. I took the train to the World Trade Center stop only a half-hour earlier. I heard the plane crash into Tower 2 and carried on stuffing envelopes like nothing happened. I evacuated my building and looked up at the double-landmark I knew and trusted as my compass in New York City on fire. I was almost hit by a smoldering cell phone case that someone was likely wearing on their belt when they died. I thought the world was coming to an end.

But it didn’t. And here we are. We got revenge on the people who caused it (as well as a whole lot of people who had nothing to do with it). Presidencies were won and lost. The Right went back to hating New York for being a bastion of moral depravity. The city rebuilt. And September 11 is just a normal day anymore.

This anniversary makes me feel so lonely. It doesn’t seem like anyone else feels as intensely as I do about today, not after almost twenty years. And how would anyone know how I felt? I’m pretty good at hiding it. Most of the people I’ve met over the past ten years have no idea what I went through that day. I don’t have anybody to talk to about it, and even if I did, I don’t know what I’d say. I can’t even write a coherent blog post after counting down to today working on it.

It’s been a long time. Never Forget.

Memories Fade, Part 1

I don’t want to be the guy who dwells on bad news and trauma, but this is something I’ll never forget. Part of it is because I literally watched it happen, and eighteen years isn’t enough to erase those images and those smells from my memory. I don’t think of it often as time has gone on, but on this date, I always do, and I feel really lonely anymore.

Nobody checks to see how I’m doing whenever this day comes around, a day I start feeling the dread for around late August. (Although, to be fair, hardly anybody I’ve met over the past ten years knows about my experiences with it.) (Also, I’m willing to bet that the people who are aware of it don’t know what to say or assume that I don’t want to talk about it.) I’d be happy to talk about it, but that’s not the kind of thing you can just bring up, especially given how complicated the emotions are attached to it.

And suddenly it arrives, and it’s nothing. There’s not a lot about it on social media anymore, and on the news, it’s mentioned pretty casually, before moving onto the next dumb-ass tweet from our president. But this was the defining event of twenty-first-century America. This mess we’re in right now directly ties back to what was planned in that cave almost twenty years ago. (September 11 led to the Iraq War, which was responsible for the election of Barack Obama, which was responsible for the election of Donald Trump and everything that has come with him. That’s just simplifying it.) Three thousand people died that day. Three hundred police and firefighter ran into the buildings I was running from, and they paid the price for their bravery. How do you forget that?

I’m sorry. I just hate this day with a passion, and it’s just weird to me that it’s no big deal anymore.

Sister Act

I haven’t had any contact with one of my sisters for a year to the day. What weirds me out is that I don’t feel all that bad about it. I’m not sure what kind of person that makes me.

You have a friend or relative like this. They’re the ones who say political opinions you find objectionable, and then defend their point-of-view in the nastiest way possible, using every fallacy in the book, and then pouncing on any admissions you make on the occasions they have a point and using this as a means of negating your entire argument. When you fight back against what they’re saying, they accuse you of trying to silence their opinions. In short, they are bullies.

I hate bullies. My Evil Sister is a bully. She is the kind of person who imagines herself telling “the truth to power” or some self-aggrandizing bullshit like that. I don’t even know if she believes what she says; it’s almost as if she is daring people to argue with her. Every time I would see a status update or a comment on one of mine, I would clench up a little. There came a point, however, when I decided that I needed to stop.

You see, thanks to the bravery and encouragement of my wife, I’ve learned to break off contact with people who make me uncomfortable. In the Facebook era of being “friends” with even with that lab partner from junior high, this is kind of difficult. But the fact is, it doesn’t matter your history—if you don’t like a person anymore, they’re not your friend. I cannot tell you how utterly liberating this is.

When I began doing this back in 2005, it was extremely difficult, so much so that I had to justify to myself why. The guy in question was my best friend throughout high school. In the past when I behaved like a drunk as a bipolar, going to highs, wherein I was a selfish-but-charming douchebag, to lows, where I was a self-pitying Eeyore, he stuck around because he knew I’d even out and be the person he enjoyed. And yet, as I got older, I couldn’t stand to be around him anymore. And then I was advised, by my wife and by my therapist that I didn’t have to.

My usual method on Facebook is this: I block offensive status updates in an attempt to ignore them. When the offender rudely attacks me for something I say on my wall, I defriend them. Evil Sister had hit the first stage, which is where I had intended to keep her (she is my immediate family and shouldn’t be disowned). However, thanks to the miracle of that wonderful Facebook sidebar that allows you to see who comments on stuff, I discovered something she said that was too much.

On September 11, 2001, a band of terrorists bombed the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, using an otherwise innocuous device—i.e. the passenger airplane—as a weapon. Most Americans are still processing what this has meant to us and to our world.

Yes, I was there. But that doesn’t make my memories superior to others. On September 11, 2011, a friend in Albuquerque reflected movingly on his first trip to the USS Arizona in Hawaii, when he discovered that it was more than just a tourist destination—it was a tomb—and how that paralleled a reaming he received from a friend for requesting a jar of WTC ashes as a memorial. Another friend wrote an essay, entitled “My Narrative,” about the fear and isolation she’d felt in Colorado as the news barely trickled in over the sound of evacuations. I wrote a piece about how something as ordinary as a statue had been taken from me, using it as a metaphor for how my day-to-day life had been changed.

Evil Sister for her part, accused everyone—everyone—who shared their “narratives,” (she used the word narratives very specifically) of trying to exploit the occasion to make it all about them—“it doesn’t matter how close you were.” This was a pretty direct, passive-aggressive swipe at me. It was a passive-aggressive swipe against her friend who wrote “My Narrative*.” It was an indirect swipe against my wife, who frequently spends months in Afghanistan, her job being to prevent this from ever happening again. It’s a swipe against the friend I was visiting that very day, a New York firefighter who lost literally dozens of the colleagues who ran into a burning skyscraper when the rest of us ran away from it. When I responded, in the gentlest terms possible (“I am disappointed and saddened that you feel this way, and that this is how you chose to express it.”), her response to me was predictable, but infuriating (“Oh, I forgot, you’re the only one who’s allowed to have an opinion.”). I informed her privately that I would not speak to her unless she apologizes, and that I don’t anticipate this ever happening. She (as I was told later) cussed me out behind my back and told me that I “always had to be right,” and told me that she didn’t care if she never heard from me again**.

And so, after a year of stubborn silence, I’ve concluded that the only thing I’m pissed off about is how my family, who understandably don’t want to take sides, talks about the incident as if both of us are at fault. We are not equal here. I’m not perfect, but I am not an asshole. I do not treat people with disrespect and venom, nor do I expect my negativity to go unchallenged.

I don’t miss my sister. I miss what she used to be—my favorite play partner when I was a child. I also miss the teenage version of the friend I mentioned earlier who now thinks that women who use birth control are sluts. Time has marched on, and so have I.

But I still feel uneasy. I feel like I could have handled this differently. I wonder if maybe I am the asshole. I won’t discuss this with the people who witnessed this, because I don’t want to put them in an awkward position, so I feel alone. And yet, as I said, I don’t like bullies. I’ve dismissed at least five old friends, including my one-time best friend, for saying less.

My life, as a result, has much less negativity than it used to. It’s also missing my sister. I’m very confused. And I will be for a long, long time.

* On this particular friend’s birthday, Evil Sister complained in her status about how she hates it when, on friends’ birthdays, her feed gets clogged up by birthday wishes. As maid of honor at this friend’s wedding, Evil Sister accused her of being a “bridezilla,” because this friend wanted to go to a tanning booth to get rid of some of those lines that had built up over the summer, which would have ruined the aesthetic of her strapless dress. Evil Sister is not a very good person, is what I’m trying to say.

** There are a lot of complications, of course, regarding the parallel and perpendicular relationships my parents have with their siblings, as well as my relationship with my niece. I won’t go into these, because I have rambled long enough.

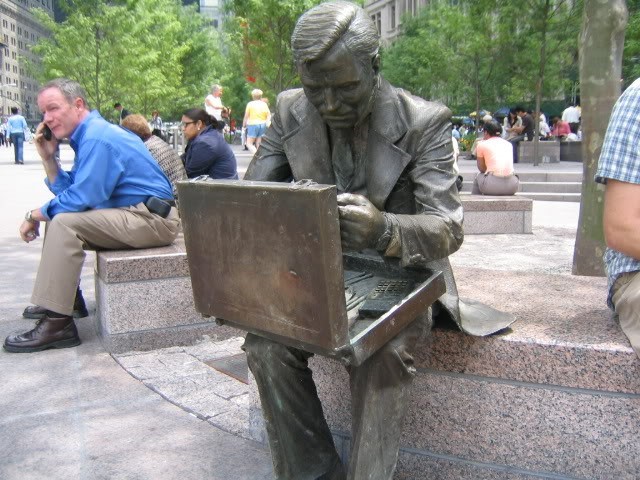

It’s Funny How We Never Look Up

I first met him that August. He sat in a park at One Liberty Plaza, New York, New York, tucked in a corner, glancing into his briefcase. He lived in harmony with the workers and tourists meandering through the area; he paid them no mind, nor they him.

At that time, autumn was creeping up on me like it always did, promising cooler air and brighter colors. Autumn was always good to me. I met my girlfriend at the time in the autumn. And years before, I’d met the woman I would eventually marry, also in the autumn.

This fall was especially welcome, especially after a summer of unemployment and unhappiness. I’d finally been granted temporary work throughout the file vaults of various banks in the financial district. I spent my lunch breaks in the park at One Liberty Plaza, smoking cigarettes and trying to draw; the latter was particularly galling, inasmuch as I seemed to have forgotten how.

One day I glanced around the park, looking for inspiration that wasn’t in this anatomy book that seemed to be the source of my frustration, and there he was, sitting on a marble step in the shade. I wondered who he was. I wondered what he was thinking. Was he relaxing, or was he about to stand up? And what was in his briefcase? Was it his lunch?

As the days of tedious filing stretched into weeks, I crept ever-so-closer and peeked over his shoulder—subtly, so as not to offend him. I remember seeing an adding machine, and a few other items. But for the life of me, I don’t recall what these other items were, only that they were archaic.

The last time I saw him, I stood up from the bench, tossed my sketchbook (weakened from the stress of erasers and my dissatisfaction) into my satchel, and dropped a quarter into a payphone. My girlfriend’s thirtieth birthday was that Thursday, and I was trying to arrange something fun; she hadn’t been my biggest fan over the past several months, and I needed to do something to fix that.

The last time I saw him was on a Monday, because on Tuesday, this happened:

I’d originally wanted to write an essay about how much this country has changed in the past ten years—about how we’ve lost our way; about the silly phrases I used to love (i.e. “Bring ’em on” and “Dodged a bullet”) but no longer feel comfortable employing, as they have been soiled by those who have no concept of the value of a human life; about the collective, parasitic rage from that day that has turned us against cultures we don’t understand, against our own freedom, against our government, and against ourselves; about lost hope; about fear …

And then I began running across never-before-seen photos from that day, begging the question: has somebody been sitting on them for ten years so they could release them for a big anniversary? And TV specials and stories and interviews on NPR and essays about what we’ve been up to over the past ten years … and stories from celebrities about what they were doing that morning. And I know that by noon on Sunday, we will have moved on to whatever it is we’re going to be saturating the media with this next cycle. It’s like the anti-Christmas.

So I wasn’t going to participate. Regardless of everything I went through that day, I wasn’t going to participate. And then I remembered him.

He’s since been moved around to museums and other parks. Now he’s been returned to where he once was, but in a prominent spot. I could go see him again, but it wouldn’t be the same. Nothing has been the same.

I prefer to remember him from that late summer, when he and I were both alone, and we liked it that way.